Introduction to Venezuela's Economy and Productivity

Venezuela, once hailed as one of Latin America's wealthiest nations in the mid-20th century, has experienced a dramatic economic transformation largely shaped by its heavy dependence on oil exports. This reliance on petroleum, which historically accounted for over 95% of the country's export earnings, fueled rapid growth during oil booms but also sowed the seeds for vulnerability and productivity stagnation. In the 1970s, following the Middle East oil embargo, world oil prices quadrupled, leading to a surge in Venezuelan government revenues and enabling expansive social programs and imports. However, this "petrostate" model, often characterized by the "resource curse" or Dutch disease, diverted investment from non-oil sectors , causing industrial production to plummet from around 50% of GDP in 1990 to just 24% by 1999 .

The economy's overdependence on oil became a critical liability as global prices fluctuated and domestic mismanagement intensified. From a peak GDP of approximately $372.59 billion in 2012 , Venezuela's economy contracted sharply, shrinking by an estimated 75% between 2014 and 2020 due to plummeting oil production, underinvestment, and external factors like U.S. sanctions. Oil output, which once exceeded 3 million barrels per day, fell to under 1 million barrels by the mid-2010s, exacerbating hyperinflation, shortages, and a humanitarian crisis. This decline in productivity is starkly illustrated by labor productivity trends, which dropped by 32.37% year-over-year in 2019 alone , reflecting broader inefficiencies in resource allocation and institutional erosion.

In recent years, under President Nicolás Maduro, there have been claims of recovery, with reported GDP growth of 9% in 2025 and projections of 7% for 2026 , driven by efforts to revive oil production and attract private investment through piecemeal liberalization. However, challenges persist, including structural weaknesses, potential hyperinflation risks, and ongoing dependence on oil amid global energy transitions. This case study examines Venezuela's productivity trajectory, highlighting the interplay of policy decisions, resource management, and external pressures that have transformed a once-prosperous economy into a cautionary example of petrostate fragility.

Historical Trends in Productivity

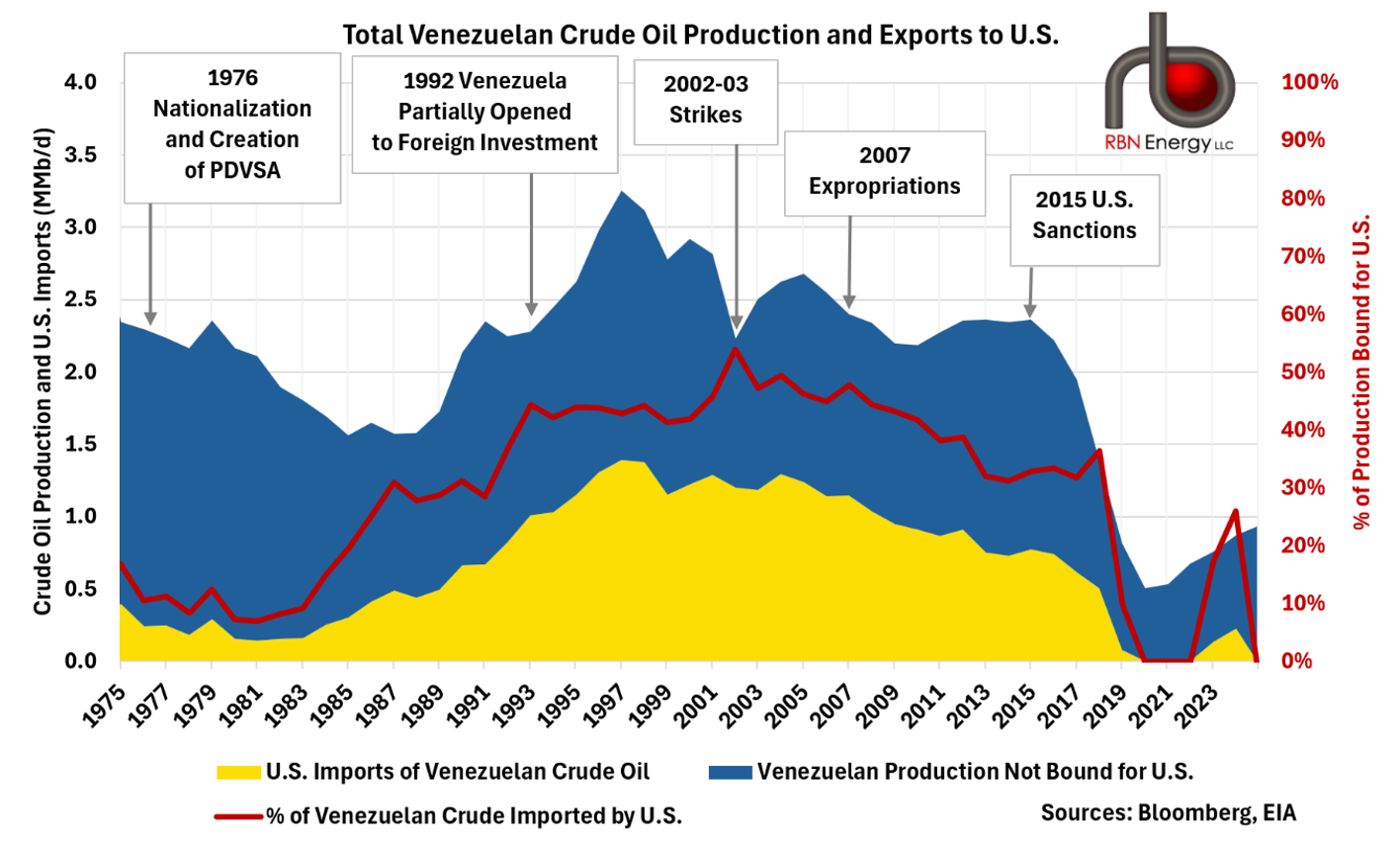

Venezuela's productivity trends over the past several decades reflect a dramatic arc from resource-fueled prosperity to profound economic contraction, largely tied to its oil-dependent economy. In the mid-20th century, particularly during the 1960s and 1970s, the country experienced robust growth driven by oil booms. Between 1960 and 1970, oil production increased by 30%, while labor productivity surged by 125% , positioning Venezuela as one of Latin America's wealthiest nations with the highest growth rate and lowest inequality in the region during the 1970s. Oil production peaked at around 3.5 million barrels per day in the 1970s, accounting for over 7% of global output and fueling per capita GDP that was several times higher than many neighbors . This era saw total factor productivity (TFP) contributing positively to growth, with high oil prices enabling expansive public spending and infrastructure development.

The 1980s marked the beginning of a slowdown as oil prices softened globally, exposing vulnerabilities in the rentier model. Productivity growth decelerated, with non-oil sectors struggling under the "Dutch disease" effect, where oil dominance appreciated the currency and undermined competitiveness in manufacturing and agriculture. From 1979 to 2002, non-oil per capita GDP fell by 18.6%, primarily due to stagnant productivity outside the hydrocarbon sector, exacerbated by pro-cyclical fiscal policies that amplified boom-bust cycles . Labor productivity, measured as GDP per hour worked, began to lag behind regional peers; for example, average annual hours worked per person hovered around 1,900 in the mid-2000s, but output efficiency declined as economic diversification efforts faltered .

The early 2000s under President Hugo Chávez saw a temporary resurgence tied to rising oil prices, with GDP reaching a peak of $372.59 billion in 2012. However, this masked underlying productivity issues, as TFP levels at constant national prices began a steady decline; by 2016, TFP had dropped to 1.078 relative to a 2017 base of 1.000, and further to 0.567 by 2019 . Labor productivity growth turned sharply negative, with a 32.37% year-over-year drop in 2019 alone, compared to a 15.25% decline the previous year . GDP per person employed also fell, reaching $27,550 in recent estimates, a 7.26% decrease from the prior year .

The sharp decline accelerated around 2013, coinciding with falling oil prices, political instability, and policy missteps under Nicolás Maduro. Between 2013 and 2023, living standards plummeted by approximately 74%, closely linked to productivity collapses across sectors. Overall GDP contracted by about 80% in less than a decade, shrinking from the 2012 peak to around $79.92 billion by recent pre-2026 estimates . Oil production, a key productivity driver, fell from over 3 million barrels per day in the early 2000s to under 1 million by 2025 , due to mismanagement at Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PDVSA), underinvestment, and U.S. sanctions intensified since 2017. Non-oil productivity suffered from hyperinflation peaking at millions of percent in 2018-2019, shortages, and human capital flight, with TFP accounting for much of the collapse alongside reduced capital accumulation.

In the 2020s, tentative signs of stabilization emerged amid partial economic liberalizations and oil price recovery. The Maduro government reported GDP growth of 3-3.9% in 2024 and 9% in 2025, with projections of 7% for 2026, though these figures were contested and heavily dependent on sanction relief and oil stabilization. Labor productivity per hour worked remained low compared to Latin American averages, which saw a 32% increase from 1990-2023 , while Venezuela's lagged significantly. The January 3, 2026, U.S. intervention and capture of Maduro introduce uncertainty but could potentially halt the decline by facilitating reforms, investment, and productivity recovery in a post-Maduro era.

| Period | Key Productivity Trend | Supporting Data | Causes/Notes |

| 1960-1970 | Rapid growth | Labor productivity +125%; Oil production +30% | Oil boom, high global prices |

| 1970s-1980s | Peak and initial slowdown | GDP per capita high; Oil at 3.5M bpd (7% global) | Resource wealth, but emerging Dutch disease |

| 1979-2002 | Stagnation in non-oil | Non-oil per capita GDP -18.6% | Policy failures, lack of diversification |

| 2000s-2012 | Temporary resurgence | GDP peak $372B; TFP positive but declining | Oil price surge under Chávez |

| 2013-2023 | Sharp decline | Living standards -74%; GDP -80%; Labor productivity -32% YoY (2019) | Oil price crash, sanctions, mismanagement |

| 2024-2025 | Claimed recovery | GDP growth 3-9%; TFP at 0.567 (2019 base) | Partial reforms, oil stabilization |

| 2026 onward | Uncertain post-intervention | Potential for rebound | U.S. oversight, sanction lifts possible |

These trends underscore Venezuela's vulnerability to oil volatility and policy choices, with productivity serving as a barometer for broader economic health.

Key Economic Indicators

Venezuela's key economic indicators illustrate a trajectory of extreme boom and bust, overwhelmingly influenced by oil revenues, policy decisions, and external factors. The economy expanded rapidly during high oil price periods but suffered one of the most severe contractions in modern economic history from the mid-2010s onward.

Nominal Gross Domestic Product (GDP) peaked at approximately $381.29 billion in 2012 (some sources cite $372.59 billion), driven by oil prices above $100 per barrel during the late Chávez era. Subsequent years saw catastrophic declines amid falling oil prices, hyperinflation, sanctions, and mismanagement, with GDP bottoming out around $43-44 billion in 2020. Partial recoveries emerged in the mid-2020s through limited liberalizations, higher oil output (partly via Chevron operations), and dollarization effects, pushing GDP to an estimated $82.77 billion in 2025 per IMF data. As of January 5, 2026, following the U.S. military operation on January 3 that captured Nicolás Maduro and his wife, indicators are highly volatile, with potential for short-term disruptions but longer-term upside from sanction relief and oil sector revival.

GDP per capita mirrored this pattern, reaching about $12,901 at the 2012 peak. It plummeted during the crisis, falling to low points in the early 2020s , and stood around $3,103 in 2025 estimates (IMF), reflecting persistent low productivity and population decline from emigration.

Labor productivity metrics underscore structural inefficiencies. In earlier decades (e.g., 1960s-2000s), Venezuela's GDP per hour worked was only slightly higher (3-4%) than U.S. levels or marginally above Latin American averages , buoyed by oil rents but hindered by limited diversification. By the crisis peak, it lagged significantly due to capital deterioration, skilled worker emigration, and sector disruptions. TFP declined sharply post-2010s, contributing heavily to output losses alongside reduced inputs.

Growth rates varied wildly: double-digit expansions in boom years gave way to contractions exceeding 30% annually (2017-2020). Recent years showed contested recoveries, with official claims of high growth (e.g., 8.71% year-over-year in Q3 2025) contrasting IMF estimates of modest figures like 0.5% for 2025 overall . Other indicators include extreme poverty rates over 50%, unemployment fluctuations, and inflation stabilizing from hyperinflationary peaks but remaining elevated into 2025 .

| Indicator | Peak (circa 2012) | Crisis Low (circa 2020) | 2025 Estimate | Notes/References |

| Nominal GDP (USD billion) | 372.59–381.29 | ~43–44 | ~82.77 | IMF, World Bank, Macrotrends |

| GDP per Capita (USD) | ~12,901 | ~1,500–2,000 | ~3,103 | IMF, Macrotrends |

| Annual GDP Growth (%) | +5–20% (boom periods) | -30% | 0.5–8.71% (IMF vs. official) | IMF, Trading Economics |

| Labor Productivity (GDP/hour worked vs. LatAm) | Slightly above average | Significantly below | Persistently lagging | Development accounting studies, Penn World Table |

See the table references below

- Nominal GDP (USD billion): IMF , World Bank ,Macrotrends

- GDP per Capita (USD): IMF , Macrotrends

- Annual GDP Growth (%): IMF , Trading Economics

- Labor Productivity (GDP/hour worked vs. LatAm): Development Accounting Studies, Penn World Table

The table above highlight how oil dependence magnified Venezuela's vulnerabilities, transforming resource abundance into economic fragility. The post-Maduro landscape as of early 2026 presents a pivotal opportunity for indicator improvement through reforms and international engagement, though success remains contingent on stable transitions.

Factors Affecting Productivity Decline in Venezuela

Venezuela's productivity decline represents a multifaceted crisis rooted in endogenous policy failures and exogenous pressures, transforming a once-prosperous oil-rich nation into an emblem of economic distress. The interplay of political instability, economic mismanagement, external sanctions, and systemic corruption has eroded productive capacity across sectors, leading to a cumulative GDP contraction of over 80% since 2013 and a 74% drop in living standards . These factors have compounded the "resource curse," where oil dependence amplified vulnerabilities without fostering diversified growth.

Political Instability and Nationalizations

Political turmoil, particularly under the Chávez and Maduro regimes, has been a primary driver of productivity erosion. Widespread nationalizations, over 1,200 companies expropriated since 2007, including key industries like oil, steel, and agriculture; discouraged private investment and led to operational inefficiencies. These actions, intended to redistribute wealth, instead resulted in mismanagement, with nationalized firms experiencing sharp productivity drops due to bureaucratic control and lack of expertise . For instance, in the oil sector, forced partnerships with state-owned integrated oil and gas company, PDVSA, reduced foreign investment, contributing to a 70% decline in production from 3 million barrels per day in the early 2000s to under 1 million by 2025. Broader instability, including protests and governance breakdowns, further stifled economic activity, with chronic shortages and business closures amplifying unemployment and underutilization of labor. The 2024 disputed election and ensuing unrest exacerbated this, though Maduro's capture in 2026 could pave the way for stability if transitional governance restores investor confidence.

Hyperinflation and Economic Mismanagement

Hyperinflation devastated productivity by eroding purchasing power, distorting prices, and incentivizing informal economies . Triggered by excessive money printing to finance fiscal deficits averaging 16.8% of GDP from 2014-2019; this led to widespread shortages of essentials, forcing businesses to halt operations and workers to prioritize survival over productivity. Real wages collapsed, with minimum wages losing over 99% of value, resulting in a brain drain of over 7 million emigrants since 2015, depleting skilled human capital. Price controls and currency manipulations further discouraged production , as firms faced losses selling below cost. By 2024, inflation had stabilized somewhat through partial dollarization, but lingering effects persisted into 2025, with risks of resurgence if exchange rates deteriorated. Post-2026, U.S. oversight might stabilize monetary policy, though immediate volatility could arise from regime change.

U.S. Sanctions and External Pressures

Intensified U.S. sanctions since 2017, targeting PDVSA and oil exports , significantly constrained productivity by limiting access to finance, technology, and markets. These measures, including bans on Venezuelan oil imports to the U.S. and secondary sanctions on third-party dealings, accelerated oil production declines, monthly output fell nearly five times faster post-2017 than before ; exacerbating fiscal shortfalls and infrastructure decay. Exports, which comprised 95% of foreign earnings, dropped sharply, freezing $7 billion in assets and hindering imports of essential inputs for non-oil sectors. While domestic policies initiated the crisis, sanctions amplified it, contributing to a 40% additional GDP drop per some estimates. Partial relief in 2023-2025, such as Chevron exemptions, boosted output modestly, but full enforcement by late 2025 paralyzed tanker movements. Maduro's 2026 capture, framed as a law enforcement action, could lead to sanction lifts, potentially revitalizing oil exports and productivity, though global oil prices dipped initially amid uncertainty.

Corruption and Institutional Decay

Endemic corruption has undermined productivity by diverting resources, degrading infrastructure, and eroding human capital. Venezuela ranks among the world's most corrupt nations (14/100 on the 2021 Corruption Perceptions Index) , with graft in PDVSA and public sectors siphoning billions; estimates suggest $300-500 billion lost since 1999 . This has led to neglected maintenance of oil refineries, power grids, and transportation, causing frequent blackouts and operational halts that reduce output efficiency. Corruption incentives, fueled by exchange controls and subsidies since 2003, fostered kleptocracy, with military involvement in smuggling and contracts exacerbating inequality and deterring foreign investment. Human rights violations tied to corruption further drove emigration, depleting skilled workers and institutional knowledge. The 2026 intervention targets Maduro's narco-terrorism charges, potentially disrupting corrupt networks but risking power vacuums if not managed inclusively.

| Factor | Key Impact on Productivity | Period of Peak Influence | Mitigating/Amplifying Developments |

| Political Instability & Nationalizations | Investment deterrence, operational inefficiencies, sector declines | 2007-2025 | Post-2026 transition could restore confidence |

| Hyperinflation | Wage erosion, shortages, brain drain | 2018-2019 | Partial stabilization via dollarization |

| U.S. Sanctions | Export restrictions, finance access limits, production drops | 2017 onward | Potential 2026 relief post-capture |

| Corruption | Infrastructure decay, resource diversion, human capital loss | 1999-2025 | U.S. intervention targeting graft |

These interconnected factors highlight how policy choices and external forces perpetuated decline, with the 2026 events offering a potential inflection point for recovery if reforms address root causes.

Oil Sector Case Study

Overview of Venezuela's Oil Sector

Venezuela possesses the world's largest proven oil reserves, estimated at approximately 303 billion barrels, primarily concentrated in the Orinoco Belt , which holds extra-heavy crude oil. This resource abundance has historically positioned the oil industry as the cornerstone of the economy, generating over 95% of export earnings and funding extensive social programs during boom periods. Managed predominantly by the state-owned PDVSA, the sector's productivity has been pivotal to national output. However, despite these vast reserves, productivity has plummeted due to a confluence of mismanagement, technical challenges, and external pressures, transforming potential wealth into a paradigm of the "resource curse." The sector's decline has directly contributed to broader economic contraction, with oil production serving as a key determinant of TFP and capital accumulation in the economy.

Historical Production Trends

Venezuela's oil production history reflects cycles of expansion and collapse tied to global prices, policy shifts, and operational efficiencies. In the 1970s, following nationalization, output peaked at around 3.5 million barrels per day (bpd), representing about 7% of global supply and driving rapid economic growth. Production stabilized in the late 1990s and early 2000s at over 3 million bpd, with PDVSA's own output reaching an all-time high of 3.235 million bpd in 2008 . However, declines accelerated post-2008, with output falling to 2.394 million bpd by that year and further to under 1 million bpd by the early 2020s due to chronic underinvestment and disruptions. By mid-2016, production had dropped by 755,000 bpd in just months, and recent data shows fluctuations around 956,000-1.142 million bpd in late 2025 , far below potential capacity. This trajectory underscores a shift from productivity gains during open foreign investment eras to stagnation amid state control.

Mismanagement at PDVSA

PDVSA's mismanagement under the Chávez and Maduro administrations has been the primary culprit in the sector's productivity collapse. Political purges, including the dismissal of 18,000 skilled workers in 2003 following a strike, dismantled institutional expertise, replacing it with politically aligned but inexperienced personnel. Corruption and embezzlement siphoned billions, estimates range from $300-500 billion lost since 1999; diverting funds from maintenance and reinvestment. Underinvestment in infrastructure led to aging facilities , frequent breakdowns, and environmental degradation, while PDVSA's role as a fiscal cash cow for government spending exacerbated deficits during low-price periods. Nationalizations of foreign assets deterred international partnerships, reducing technology transfers and capital inflows. These factors, combined with U.S. sanctions since 2017, accelerated the decline, though domestic policies initiated the crisis.

Challenges with Heavy Oil Reservoirs

A significant portion, nearly 60% of Venezuela's production originates from the Orinoco Belt, home to extra-heavy crude that is highly viscous and dense, akin to tar. Extraction requires advanced techniques like steam injection and diluents, which are energy-intensive and costly, increasing production expenses compared to lighter crudes. The U.S. Geological Survey estimates 900-1,400 billion barrels in place, but recoverable amounts (380-652 billion) depend on technology and investment, which have been lacking. Sanctions and mismanagement halted steam-assisted projects and upgrading facilities, leading to well shutdowns and a 25% output drop in the Orinoco Belt by late 2025. Environmental impacts, including river pollution from spills , further complicate operations.

Total Factor Productivity Determinants

Studies on TFP in Venezuela's oil sector reveal a negative correlation with oil revenues, where rentier dynamics foster inefficiencies rather than innovation. TFP declines accounted for half of the post-2013 economic collapse , driven by reduced capital per worker and non-oil productivity spillovers. In the oil sector specifically, TFP evolution explains output behavior, with falls linked to scant investment and exogenous shocks like price volatility. Comparative analyses show Venezuela's TFP lagging behind peers, exacerbated by the sector's dominance without diversification.

Impact on Overall Productivity

The oil sector's woes have rippled through the economy, reducing fiscal revenues, inducing hyperinflation, and prompting human capital flight, all of which depress national productivity. Declining output has limited foreign exchange for imports, stalling non-oil sectors and perpetuating dependence.

Recent Developments (2023-2026)

Partial recoveries in 2023-2025, aided by sanction waivers for firms like Chevron, boosted production modestly to around 1.1 million bpd by late 2025. However, renewed U.S. enforcement in late 2025 led to export blockages and field shutdowns. The January 3, 2026, U.S. intervention and Maduro's capture have introduced volatility : oil prices swung initially, with U.S. oil shares rallying on prospects of sector access. Trump administration plans emphasize U.S. oversight to rebuild infrastructure, potentially increasing output quickly with investment, though hurdles include corruption, legal debts (e.g., ConocoPhillips $12 billion), and geopolitical risks. China's $19 billion loans tied to oil add complexity.

| Period | Production (million bpd) | Key Factors | Notes/References |

| 1970s | ~3.5 | Nationalization boom | High global share |

| Early 2000s | >3 | Foreign investment | Peak PDVSA output |

| 2008 | 2.39-3.235 | Pre-crisis high | Tenth-highest globally |

| 2016 onward | <1 (declining) | Sanctions, mismanagement | Acute drops |

| Late 2025 | ~0.956-1.142 | Partial recovery | Orinoco focus |

| Post-Jan 2026 | Uncertain (~1.1) | U.S. intervention | Potential rebound |

This case study exemplifies how institutional failures and resource-specific challenges undermined productivity, with the 2026 events offering a potential turning point for revival.

Non-Oil Sectors and Diversification Efforts

Venezuela's non-oil sectors encompassing agriculture, manufacturing, services, and emerging areas like mining and renewables; have historically been marginalized by the dominance of oil exports, which accounted for over 95% of foreign earnings and stifled broad-based productivity through "Dutch disease" effects, such as currency overvaluation and resource misallocation. These sectors endured severe productivity declines amid economic crises, including shortages, price controls, hyperinflation, and investment shortages from the mid-2010s onward. The productive structure remained largely unchanged from 1950 to 2012, with non-oil activities contributing minimally to growth and exports hovering at negligible levels (e.g., 0.1% of firm sales pre-2020). However, partial liberalizations and sanction adaptations in the 2020s spurred modest diversification, with non-oil exports rising to 8% of firm sales by 2020 and showing further gains by 2025. Despite these shifts, productivity remains low, with sectors like manufacturing and agriculture operating at fractions of capacity due to infrastructure decay and human capital loss.

Agriculture Sector

Agriculture, employing about 10.63% of the workforce in 2023 , has suffered profound productivity setbacks from land expropriations, input shortages, and climate vulnerabilities, leading to output far below potential. Key crops like maize, rice, and cocoa saw declines during the 2010s crisis, with production hampered by fertilizer scarcity and irrigation deficits. By 2024, crop output recovered slightly above the five-year average, driven by partial market openings and resilient varieties, with maize production projected to rise in 2025/2026 amid expected abundant precipitation in early 2026. Export-oriented products like shrimp and cocoa contributed to non-oil exports, reaching markets in 47 countries by 2023. However, the sector remains dormant in broader terms, with persistent challenges like dormant farmland and low mechanization limiting productivity gains. Opportunities for 2025-2026 include climate-resilient crops gaining 15% more acreage, potentially boosting yields if infrastructure investments materialize post-intervention.

Manufacturing Sector

Manufacturing, part of the 21.26% industrial employment in 2023 , includes heavy industry products like aluminum, steel, and textiles, but has been crippled by raw material shortages, power outages, and expropriations that reduced capacity utilization to below 20% at crisis peaks . GDP composition data for 2023 shows mining, manufacturing, and utilities at 30.64%, yet productivity lagged due to lack of diversification and investment. Recent efforts, such as partial privatizations and dollarization, supported modest recoveries, with manufactured goods like textiles and aluminum featuring in the $3 billion non-oil exports in 2023. By 2025, non-oil economic activity rose 3.9% , though industrial sectors continued to suffer from sanctions and infrastructure woes. The 2025 budget of $22.7 billion allocated funds for infrastructure, potentially aiding manufacturing revival, but constraints like state dominance and regulatory gaps persist. Post-2026, U.S.-led reforms could attract foreign capital to rebuild supply chains, addressing erosion in equipment and vendor ecosystems.

Services Sector

The services sector, absorbing 70.91% of employment in 2023 , includes trade, tourism, and finance, but productivity has been undermined by hyperinflation, informalization, and migration-driven labor shortages. Growth in non-oil activity reached 3.9% by mid-2020s , supported by partial liberalizations allowing dollar transactions and private sector expansions. However, services remain vulnerable to power grid failures and regulatory instability, with tourism hampered by security concerns and infrastructure decay. Emerging opportunities in renewables, such as private solar adoptions by firms like Nestlé , hint at service-oriented diversification. Overall, the sector's productivity trails regional peers, reflecting broader economic contraction.

Diversification Efforts

Efforts to diversify beyond oil intensified in the 2020s amid sanctions, with non-oil exports surging 87.66% in the first four months of 2025 compared to 2024 , driven by agriculture, manufacturing, and mining. The 2025 budget emphasized infrastructure and renewables, including a 50 MW solar project in Mérida with Chinese collaboration, aligning with global decarbonization. Mining in gold, nickel, and coltan offers potential, though illegal activities and environmental issues constrain progress. BRICS alliances and partial U.S. sanction easings in 2023 facilitated foreign investment, but geopolitical risks and underdeveloped regulations limited impact. IMF forecasts for 2025 pegged non-oil growth at 3%, underscoring gradual shifts.

Recent Developments (2023-2026)

From 2023-2025, diversification gained traction, with non-oil exports reaching $3 billion in 2023 and strong growth in 2025, amid political reforms for participatory democracy. However, sectors like construction and livestock remained dormant, forecasting a tough 2026 under prior constraints. The January 3, 2026, U.S. operation, capturing Maduro and signaling U.S. oversight of oil, could indirectly benefit non-oil sectors by lifting sanctions, enabling capital inflows for infrastructure and green initiatives. Risks include short-term economic volatility, migration spikes, and alliance strains with Russia and China, potentially delaying productivity rebounds.

| Sector | Employment Share (2023) | Key Productivity Challenges | Recent Diversification Gains | Notes/References |

| Agriculture | 10.63% | Input shortages, climate risks | Maize production rise projected 2025/2026; Exports (cocoa, shrimp) | FAO |

| Manufacturing | 21.26% (industry incl.) | Capacity underutilization, outages | Aluminum/textiles in $3B non-oil exports (2023) | Statista |

| Services | 70.91% | Informalization, labor flight | Partial recoveries via dollarization | Statista, Lloyds Bank |

| Mining/Renewables | Part of industry | Illegal mining, regulations | 50 MW solar project; Critical minerals potential | AInvest |

See the table references below

- Agriculture: FAO

- Manufacturing: Statista

- Services: Statista , Lloyds Bank

- Mining/Renewables: AInvest

These efforts highlight incremental progress amid structural hurdles, with the 2026 intervention potentially catalyzing sustainable diversification if inclusive reforms follow.

Government Policies and Their Impact

Venezuela's government policies under Presidents Hugo Chávez (1999-2013) and Nicolás Maduro (2013-present) have profoundly shaped the nation's productivity trajectory, often exacerbating the vulnerabilities inherent in its oil-dependent economy. These policies, rooted in "21st-century socialism," emphasized social redistribution, state control, and resource nationalism, but frequently led to inefficiencies, distortions, and economic collapse. Pro-cyclical fiscal spending where government expenditures rose with oil revenues during booms and contracted sharply during busts; amplified volatility, while nationalizations, price controls, and exchange restrictions deterred investment and stifled productivity growth. The "economic merry-go-round" metaphor captures this cyclical mismanagement of oil rents in the 21st century, where political priorities over prudent economic stewardship perpetuated boom-bust cycles, leading to phases of expansion followed by contraction without sustainable development. These approaches contributed to a staggering 80% GDP contraction since 2013 , hyperinflation, and productivity declines across sectors, compounded by U.S. sanctions and internal corruption.

Policies Under Hugo Chávez

Chávez's administration pursued aggressive social and economic interventions, funded by high oil prices (often exceeding $100 per barrel), which temporarily boosted growth but sowed seeds for long-term productivity erosion. Key initiatives included the "Bolivarian missions," expansive social programs that expanded access to healthcare, education, and housing, reducing poverty by about 20% and improving human development indicators. However, these were financed through pro-cyclical spending, diverting oil revenues from productive investments like infrastructure maintenance or diversification, leading to overreliance on imports and vulnerability to price shocks. Nationalizations of over 1,200 companies, including foreign oil assets, aimed at resource sovereignty but resulted in mismanagement, reduced foreign direct investment (FDI), and operational inefficiencies at PDVSA, where production began declining post-2008 . Price controls on essentials, intended to combat inflation and ensure affordability, instead caused shortages, black markets, and disincentives for domestic production, particularly in agriculture and manufacturing. Exchange controls since 2003 distorted markets, fostering corruption and capital flight, further undermining productivity by limiting access to foreign inputs. While promoting broad participation and empowerment, these policies prioritized short-term consumption over long-term efficiency, steering industry toward domestic fulfillment without export diversification.

Policies Under Nicolás Maduro

Maduro inherited a faltering economy amid falling oil prices (nearly 50% drop in 2014) and intensified Chávez-era policies, leading to deeper productivity collapses. Continued pro-cyclical fiscal strategies resulted in massive deficits (averaging 16.8% of GDP from 2014-2019), financed by money printing that triggered hyperinflation peaking at over 1 million percent in 2018. This eroded real wages, spurred a brain drain of over 7 million emigrants, and halted business operations, directly impacting labor productivity. Mismanagement at PDVSA, including political appointments and corruption , accelerated oil output declines from 3 million bpd to under 1 million, depriving the economy of revenues and exacerbating fiscal shortfalls. Price and exchange controls persisted, worsening shortages and informalization, while partial liberalizations in the 2020s such as dollarization and limited privatizations offered modest relief, enabling non-oil growth of 3-3.9% in 2024 and claimed 9% overall in 2025. However, these were insufficient to reverse productivity stagnation, with policies often criticized for relentless class warfare, heavy-handed interventions, and failure to address corruption, which siphoned billions from public funds. U.S. sanctions since 2017 amplified impacts by restricting oil exports, though domestic policies were the primary drivers of the crisis.

The Economic Merry-Go-Round and Boom-Bust Cycles

The "economic merry-go-round" describes the 21st-century political management of oil rents, characterized by two stages : initial redistribution during high-price booms (2004-2012) and desperate survival measures amid busts (post-2013). Oil revenues were used for social spending without building sovereign wealth funds or reserves, unlike Norway, leading to amplified cycles where booms masked inefficiencies and busts exposed them. This pro-cyclicality hindered productivity by discouraging private sector innovation, fostering dependency, and causing recurrent contractions, with TFP turning negative and contributing to the largest peacetime economic collapse in history.

Impact on Productivity

These policies directly eroded productivity through multiple channels: nationalizations reduced efficiency in key sectors; controls distorted markets and incentives; fiscal mismanagement fueled inflation and instability; and corruption degraded institutions. Non-oil sectors stagnated, with per capita GDP falling 18.6% from 1979-2002 and living standards dropping 74% from 2013-2023. Labor productivity lagged regional peers, as human capital flight and infrastructure decay compounded issues. Positive aspects, like social programs empowering the populace, were overshadowed by economic distortions that failed to foster sustainable growth.

Recent Developments and Post-2026 Outlook

By 2023-2025, Maduro's government claimed recoveries through partial reforms, but warnings persisted of hyperinflation risks if exchange rates worsened. The January 3, 2026, U.S. intervention, capturing Maduro and signaling U.S. control over oil assets, marks a pivotal shift, potentially ending socialist policies and introducing market-oriented reforms. This could lift sanctions, attract Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), and stabilize fiscal management, boosting productivity, though challenges include geopolitical fallout, elite resistance, and short-term disruptions to oil revenues.

These policies illustrate how ideological priorities clashed with economic realities, perpetuating the resource curse and hindering productivity, with the 2026 events offering a potential reset.

Recent Developments (2023-2026)

Venezuela's recent economic trajectory from 2023 to early 2026 reflects a mix of partial stabilization, contested recovery claims, and profound disruption following the U.S. intervention. Amid ongoing challenges like U.S. sanctions, oil price fluctuations, and internal policy adjustments, the Maduro government touted incremental growth driven by partial liberalizations, dollarization, and limited sanction relief. However, independent assessments often painted a more modest picture, highlighting dependencies on oil revenues and risks of renewed instability. The dramatic U.S. military operation on January 3, 2026, capturing President Nicolás Maduro and signaling U.S. oversight of the oil sector, has introduced significant uncertainty, with immediate market reactions suggesting potential for rapid shifts in productivity and economic dynamics. As of January 7, 2026, developments include announcements of major oil transfers to the U.S., stock market surges , and geopolitical tensions, potentially paving the way for sanction relief and investment inflows but risking short-term volatility in currency, exports, and infrastructure.

Economic Stabilization and Growth Claims (2023-2025)

Following the acute crisis of the late 2010s, Venezuela experienced tentative rebounds attributed to adaptive measures such as informal dollarization, reduced price controls, and selective foreign partnerships, particularly in oil. In 2023, the economy grew by an estimated 5-5.5%, supported by oil price stabilization and partial U.S. sanction waivers allowing operations by firms like Chevron. This marked a shift from prior contractions, with non-oil sectors showing modest gains amid broader diversification efforts. For 2024, growth estimates varied: the Maduro government claimed 9%, while independent sources like the IMF projected 3-5.3%, reflecting a modest rebound driven by gradual oil recovery but tempered by persistent inflation and infrastructure deficits. By mid-2025, quarterly data indicated GDP growth above 6% in Q2, with annual claims reaching 9% as per Maduro's announcements, alongside projections of 7% for 2026 . These figures were often disputed, with IMF forecasts holding at 3% for 2025, citing overreliance on oil and vulnerabilities to external shocks.

Inflation, while down from hyperinflationary peaks, remained a concern, with currency woes exacerbating the crisis in early 2025 as sanctions tightened amid electoral disputes. Warnings abounded of potential hyperinflation resurgence if exchange rates deteriorated significantly, such as to 450 bolívares per dollar , underscoring dependencies on oil export stabilization and intermittent sanction relief. Overall, these years saw GDP estimates rise from around $44 billion in 2020 to $82-83 billion by 2025, but the economy remained less than half its 2013 size, with productivity gains limited by human capital flight and corruption.

The U.S. Intervention and Maduro's Capture (January 2026)

On January 3, 2026, U.S. forces executed a large-scale operation in Caracas, capturing Maduro and his wife, Cilia Flores, on longstanding charges including narco-terrorism and drug trafficking. Maduro was extradited to New York, while President Trump framed the action as a law-enforcement measure to dismantle a "narco-regime," announcing U.S. intent to temporarily oversee Venezuela's oil sector for infrastructure rebuilding and transitional stability. Vice President Delcy Rodríguez assumed acting presidency per Venezuela's Supreme Court, amid international criticism labeling the move as aggression.

By January 7, 2026, economic ramifications were unfolding rapidly. Trump announced a deal for Venezuela's interim authorities to transfer 30-50 million barrels of sanctioned oil to the U.S., to be sold at market price with proceeds controlled by the U.S. to benefit both nations, executed by Energy Secretary Chris Wright. This move aims to unlock stranded oil amid prior blockades, potentially easing U.S. energy costs and aiding Venezuelan recovery. U.S. oil company shares surged, with Trump set to meet executives from Chevron, ConocoPhillips, and Exxon on January 9 to discuss billions in investments for sector revival. Venezuela's Caracas Stock Exchange rose over 75% since the capture, pricing in anticipated sanction lifts and political stability.

Geopolitically, China condemned the "oil seizure" as a violation of sovereignty, highlighting risks to its $19 billion in oil-tied loans . Analysts note limited near-term global economic consequences but emphasize opportunities for Western firms in Venezuela's vast reserves, potentially reshaping energy markets and reversing decades of mismanagement. However, Acting President Rodríguez has rejected foreign control, creating tensions, while questions linger over the deal's legitimacy and impacts on productivity, including potential for U.S.-led reforms to boost oil output and economic diversification.

These developments underscore a fragile recovery disrupted by geopolitical intervention, with the post-Maduro era holding promise for productivity revival through reforms but fraught with risks of economic collapse if transitions falter.

Comparative Analysis

Venezuela's productivity challenges stand in stark contrast to those of its regional peers, Colombia and Brazil, as well as global oil-rich counterparts like Norway. While all these nations have grappled with resource dependencies, Venezuela's acute "Dutch disease" characterized by oil dominance leading to currency appreciation, neglect of non-oil sectors, and economic volatility has severely hampered diversification and efficiency. This phenomenon, where natural resource booms undermine manufacturing and agriculture competitiveness, has perpetuated a rentier economy in Venezuela, unlike the more balanced approaches in comparator countries. Historical data reveals Venezuela's labor productivity, measured as GDP per hour worked, lagging significantly behind peers: in 2025 estimates (constant international dollars at PPP), Venezuela stood at $15.72, compared to Colombia's $18.92, Brazil's $22.01, and Norway's $123.63. These disparities underscore institutional and policy differences, with Venezuela's mismanagement amplifying resource curse effects, while others mitigated them through diversification and prudent fiscal strategies. The January 3, 2026, U.S. intervention and Maduro's capture could alter this trajectory by facilitating reforms and sanction relief, potentially aligning Venezuela closer to successful models like Norway's, though short-term geopolitical risks loom.

Comparison with Regional Peers: Colombia and Brazil

Colombia and Brazil, as Latin American neighbors, provide apt benchmarks for Venezuela , sharing similar geographic and cultural contexts but achieving greater economic resilience through diversification. Colombia, despite its own oil sector (contributing about 40% of exports), has mitigated Dutch disease by fostering agriculture (e.g., coffee, flowers) and services, resulting in steadier productivity growth. In 2024, Colombia's GDP per capita was approximately $7,948, outpacing Venezuela's $3,103, with labor productivity benefiting from policy reforms post-1990s that encouraged foreign investment and trade liberalization. TFP in Colombia has shown positive trends, contrasting Venezuela's negative contributions to growth since the 2010s.

Brazil, Latin America's largest economy, exemplifies diversification beyond commodities like oil and soy, with strong manufacturing (automobiles, aerospace) and services sectors driving productivity. Brazil's GDP per hour worked at $22.01 in 2025 reflects investments in education and infrastructure, yielding higher human capital returns compared to Venezuela's brain drain-affected $15.72. While Brazil faces inequality issues, its institutional frameworks have better absorbed commodity shocks, avoiding Venezuela's hyperinflation and 80% GDP contraction. Both peers have leveraged regional trade agreements (e.g., Pacific Alliance for Colombia, Mercosur for Brazil) to enhance non-resource exports, a strategy Venezuela largely neglected under Chávez-Maduro policies.

Contrast with Norway: Sovereign Wealth Fund Model

Norway offers a striking counterexample to Venezuela's resource curse, having transformed North Sea oil discoveries into sustained prosperity through institutional innovation. Despite producing less oil historically (Venezuela has extracted over twice as much), Norway's Government Pension Fund Global valued at over $1.7 trillion in 2025 sterilizes oil revenues to prevent Dutch disease, investing abroad to avoid domestic inflation and currency overvaluation. This has sustained high productivity, with GDP per hour worked at $123.63 in 2025, far exceeding Venezuela's levels, supported by investments in education, technology, and non-oil sectors like fisheries and renewables. Norway's transparent governance and fiscal rules contrast Venezuela's corruption and pro-cyclical spending, which diverted oil rents to short-term social programs without building resilience. As a result, Norway avoided the productivity stagnation seen in Venezuela, where non-oil per capita GDP fell 18.6% from 1979-2002, maintaining low inequality and high living standards.

Broader Implications and Post-Intervention Outlook

Venezuela's oil dependence induced Dutch disease by crowding out non-oil investments, leading to lower TFP and labor efficiency compared to diversified peers. Institutions play a pivotal role: strong governance in Norway and partial reforms in Colombia/Brazil enabled success, while Venezuela's policy failures exacerbated vulnerabilities. The 2026 U.S. operation, including oil transfers and potential investments, could emulate Norway's model by revitalizing the sector and promoting diversification, though success depends on inclusive transitions amid reactions from allies like Brazil and Colombia.

| Country | GDP per Hour Worked (2025, Intl. $ PPP) | Key Diversification Strategy | Productivity Trend Notes |

| Venezuela | $15.72 | Limited; oil >95% exports | Sharp decline post-2013 due to Dutch disease |

| Colombia | $18.92 | Agriculture, services emphasis | Modest growth via trade reforms |

| Brazil | $22.01 | Manufacturing, agribusiness | Resilient despite inequality |

| Norway | $123.63 | Sovereign wealth fund, tech/renewables | Sustained high via prudent management |

Challenges and Opportunities

Venezuela's path to productivity recovery is fraught with entrenched challenges stemming from decades of economic mismanagement, but the dramatic events of January 2026, particularly the U.S.-led capture of Nicolás Maduro on January 3 have introduced new opportunities for transformation.

Persistent Challenges

- Human Capital Flight (Brain Drain)

- Infrastructure Decay

- Environmental and Climate Vulnerabilities

- Corruption and Institutional Weaknesses

- Geopolitical and Economic Risks

Emerging Opportunities

- Sanction Relief and Oil Sector Revival

- Private Sector Revival and Foreign Investment

- Policy Reforms and Institutional Rebuilding

- Broader Economic and Geopolitical Shifts

| Category | Challenges | Opportunities | Implications |

| Human Capital | Brain drain of 7M+ emigrants | Repatriation incentives | Transitional stability could encourage returns, boosting skills |

| Infrastructure | Decay requiring $100B+ investment | U.S.-led rebuilding | Oil transfers and FDI to accelerate modernization |

| Environment | Oil spills, climate risks | Sustainable mining/renewables | Green reforms to attract ethical investment |

| Institutional | Corruption, instability | Anti-corruption frameworks | U.S. oversight to foster trust and efficiency |

| Geopolitical | Alliance strains (China/Russia) | Sanction relief, market access | Limited global spillovers but regional shifts |

Conclusion and Recommendations

In conclusion, Venezuela exemplifies how abundant resources, mismanaged through ideological priorities and institutional weaknesses, can transform prosperity into collapse. The resource curse amplified by domestic failures rather than external factors alone; drove productivity stagnation, contrasting sharply with models like Norway's sovereign wealth fund approach. The 2026 events offer a rare opportunity to break this cycle, but without addressing root causes, history risks repeating.

Recommendations for boosting productivity include:

- Economic Diversification: Aggressively invest oil revenues in non-oil sectors (agriculture, manufacturing, renewables) via incentives for private enterprise and trade liberalization, reducing vulnerability to commodity shocks.

- Anti-Corruption Measures: Establish transparent institutions, independent audits of PDVSA, and international oversight to recover diverted funds and rebuild investor trust.

- Infrastructure Modernization: Prioritize hundreds of billions in targeted investments for power, transport, and oil facilities, potentially leveraging U.S.-led partnerships post-intervention.

- Human Capital Repatriation: Implement incentives like tax breaks and skill-matching programs to reverse brain drain, alongside education reforms to enhance workforce efficiency.

- Fiscal Prudence and Institutional Reforms: Adopt counter-cyclical policies, perhaps inspired by a sovereign wealth fund, to stabilize spending and mitigate boom-bust cycles.

- International Cooperation: Foster multilateral engagement for debt restructuring, sanction phased relief, and technical assistance, ensuring inclusive transitions that avoid power vacuums.

Ultimately, sustainable productivity growth demands political stability, rule of law, and a shift from rentier dependency to broad-based development. If harnessed effectively, the post-Maduro era could mark Venezuela's rebirth; otherwise, it risks prolonging decline. The lessons are clear: resource wealth is no substitute for sound governance.